I wrote the proposal for MacArthur’s Research and Writing Competition in early 1998 and was notified in fall 1998 that I was awarded a grant for my proposed topic, “Integrating Russia into the International Community: US Efforts, Organizational Constraints, and the Critical Role of the Russian Military,” which reflected an ephemeral, optimistic era in U.S.-Russian relations.

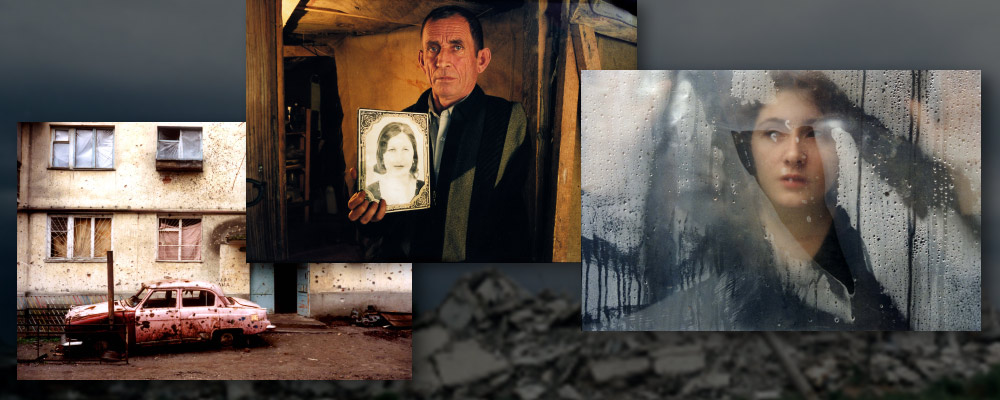

By the time the grant began in fall 1999, the relationship had soured. In March 1999, NATO bombed Serbia in an effort to stop the ethnic cleansing by Serbs of Kosovo Albanians, infuriating the Russians, and occurring weeks after NATO enlarged to include Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. In June 1999, Russian troops—those I would be studying—rushed from their barracks in Bosnia to stake out territory at the Pristina airport in Kosovo, engaging in a nail biting stand-off with NATO forces. Worst of all, just as I began research, apartment buildings in various Russian cities mysteriously blew up, terrifying citizens. Chechens were blamed although some observers felt (and still maintain) a government role in the terror. Vladimir Putin, propelled to power in part by these events, began a take-no-prisoners war in Chechnya, targeting civilians and humanitarian workers.

While I went about examining what had briefly worked in Russian military cooperation with NATO and the United States, I increasingly found myself tracking human rights violations. The findings from the grant shaped my career over the next two decades as a scholar, public policy analyst, and senior official in the Obama administration. The type of grant—one that enabled discovery and supported pure research as opposed to developing a project or organizing a conference—I found both rare and transformative.

Specifically, the rhetoric used by U.S. and NATO officials to describe the military cooperation with Russia in the Balkans as effective and professional belied systemic complicity in human trafficking by numerous international organizations, high ranking officials, troops—United Nations, Russians, and others—and U.S. contractors. After the introduction of UN and NATO peacekeepers in Bosnia in 1996, and Kosovo in 1999, the trafficking of women and girls from various parts of Eastern and Central Europe spiked dramatically. At one point, these women were being openly sold in slave markets.

When the grant ended in 2002, we were in the early days of the fight against modern slavery, the UN had adopted a legal definition of trafficking, and the State Department had established the Office to Combat and Monitor Trafficking in Persons, which provided me with a grant to continue the work I’d begun under the MacArthur grant. It allowed me to work with colleagues to promote new policies addressing human trafficking at the Department of Defense, the UN, and NATO. In 2005, I published my research in a Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) report, Barracks and Brothels: Peacekeepers and Human Trafficking in the Balkans, and testified before Congress. By 2010, as a deputy at the United States Agency for International (USAID), my team created new policies on how best to integrate combatting trafficking into development assistance, which USAID adopted in 2012. In 2015, weeks after my confirmation as a U.S. Ambassador to the UN, I helped organize the first meeting on human trafficking in the Security Council with the brave Nadia Murad, a Yezidi, telling her story of surviving ISIL. The work is unfinished; many Yezidis are still held captive by ISIL, and the news is full of stories of sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers and humanitarian workers. And yet, since adopting the Sustainable Development Goals, the global community, among other ambitions, has committed to eradicating human trafficking by 2030.

With the war in Chechnya raging when the grant ended—costing Russia little in its relationship with the West—I launched a nearly decade-long series of projects elevating the security implications of human rights abuse in Russia. I testified before Congress as far back as May 2000, drawing on MacArthur-funded research, arguing that Putin’s domestic actions and roll back of human rights posed a security threat to the United States. By 2018, Putin’s path is obvious to most; not only have numerous activists and journalists since been murdered, NGOs shuttered, and neighboring countries invaded, but the Kremlin’s goal of undermining the rule-based international order is on full display. While it feels more elusive than ever, I still find myself dreaming of a democratic Russia, driven by a new generation that has more in common with peers around the world than the corrupt cronies in the Kremlin. The post-post-Putin generation may ultimately be the one to deliver the vision many of us had 20 years ago.

Mendelson received an award of $39,000 through MacArthur’s Research and Writing Competition, which supported projects to improve understanding of key topics in global security and sustainability, as well as to broaden and strengthen the community of scholars engaged in work on these issues. Projects supported ranged in focus from migration and refugees to technological change to international peace and security. The competition ran from 1986 to 2005, during which MacArthur awarded 627 grants representing 729 researchers in 52 countries and totaling nearly $35 million.